The last time SAG-AFTRA and the WGA collectively went on strike was in 1960, and…

Never Again? The Power of Advertising to Move the Gun Debate

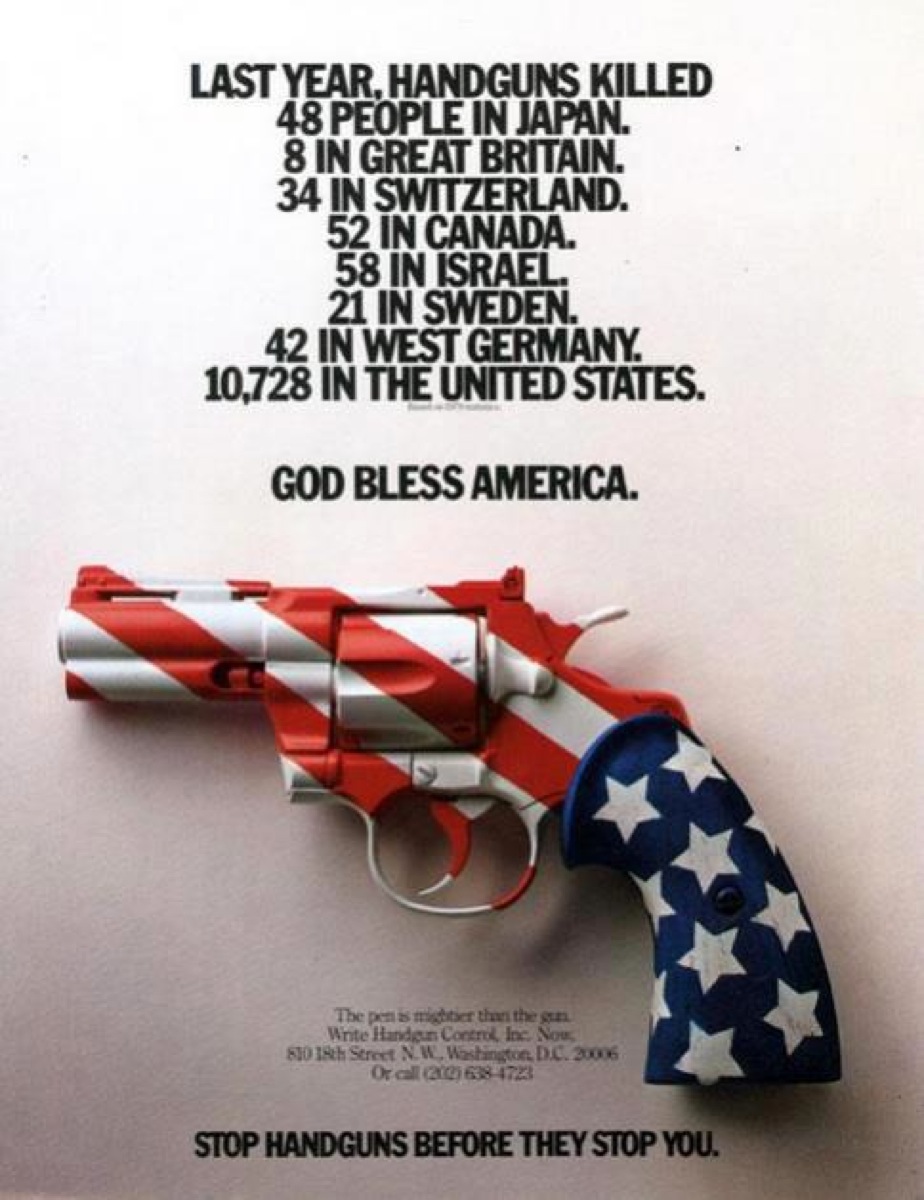

It’s a classic ad. Gun-related death statistics from around the world run in a vertical column down the page: 48 people in Japan. 8 in Great Britain. 34 in Switzerland. The list goes on, finally jumping to 10,728 in the United States. A handgun is painted red, white and blue to resemble the nation’s flag.

“God Bless America,” the text reads. “STOP HANDGUNS BEFORE THEY STOP YOU.”

That was 1981, not long after John Lennon was assassinated.

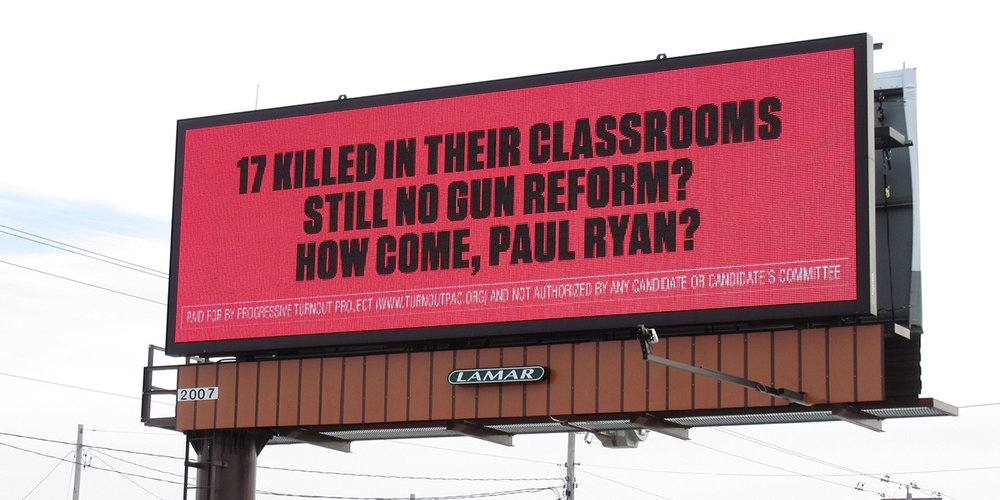

Nearly four decades later, Progressive Turnout Project, a Democratic political action committee, launched a billboard campaign inspired by 2018 Oscar nominee, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, demanding stricter gun control laws. The group called out US House Speaker Paul Ryan for repeatedly not passing gun reform legislation, particularly after the Valentine’s Day school shooting in Parkland, Fla..

Year after year, America’s gun debate continues to rage. After 28 people were killed, including 20 children, in the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, it looked as if there might be renewed momentum to enact more controls, and advertising agencies took note. Advocacy groups including Sandy Hook Promise and Everytown for Gun Safety came out with gun safety campaigns ranging from The Bill of Rights for Dumbasses to Not Our Words.

And yet, here we are six years later in the aftermath of Parkland, Florida – one of the 10 deadliest mass shootings in US history. Is gun control advertising powerful? Yes. Shocking? Often. But do ads promoting gun safety really work?

Recent events and a snapshot of gun control advertising vis-a-vis gun violence trends would suggest not. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the rate of gun deaths in the United States rose in 2016 to about 12 per 100,000 people, up from a rate of about 11 for every 100,000 the previous year. Meanwhile, the NRA ran approximately 23,700 ads in the United States in 2016, with an estimated paid media budget nearing $30 million.

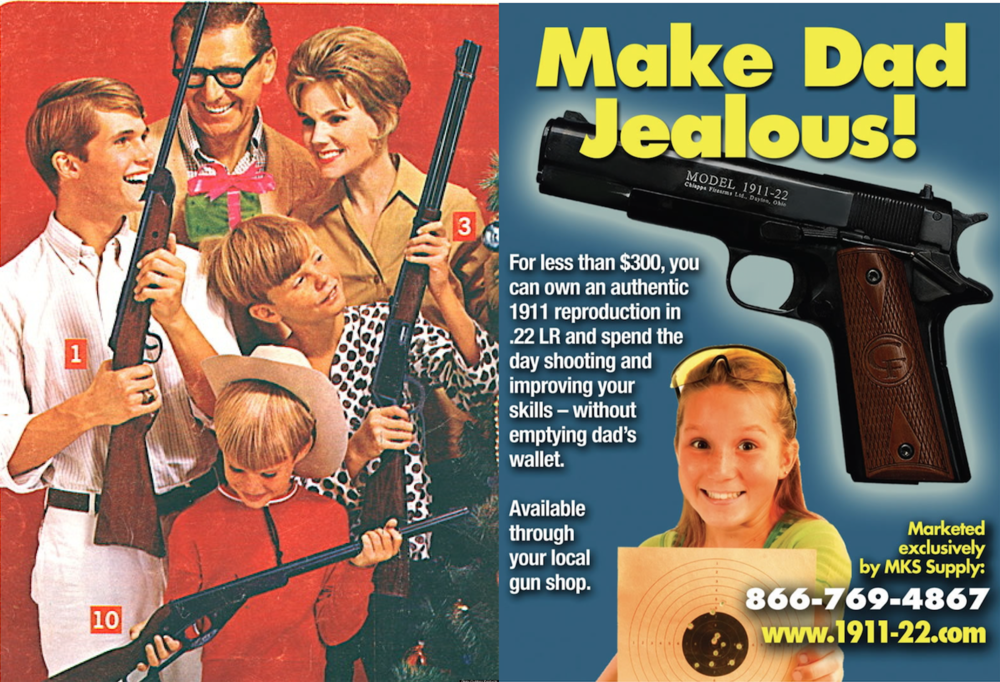

sample gun ads from the 1950’s (left) and 1980’s (right).

sample gun ads from the 1950’s (left) and 1980’s (right).

Gun advertising on behalf of manufacturers and retailers has changed over the years to reflect the national climate. In the 1940s and ‘50s, advertisers positioned gun ownership as a way to create the ideal nuclear family, even pitching them as the perfect Christmas gifts for young boys. As crime rates rose in the 1970’s through the 90’s, so did the fear factor and self-defense posture of gun ads that targeted a new audience – women and children.

Gun advertisements in the 21st century have focused on new technology and anti-government sentiment while capitalizing on the gaming industry, according to Blue Review, a Boise State University politics and media journal. ”Increasingly sinister themes in gun advertising emerged during the same era that violent first-person shooter and war games came into their heyday,” the journal reported.

In the year after Sandy Hook, gun-control groups spent $14.1 million on TV advertising — a 7:1 advantage over gun-rights organizations, which spent $1.9 million. Among others, New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg funded a $12 million national advertising campaign targeting politicians in 13 states and pushing for tighter federal regulations.

Meanwhile, gun-rights groups, led by the National Rifle Association, spent about $6.2 million on lobbying instead of advertising, according to one study. The result? Nearly two-thirds of new state laws actually eased restrictions and expanded the rights of gun owners, cited The New York Times.

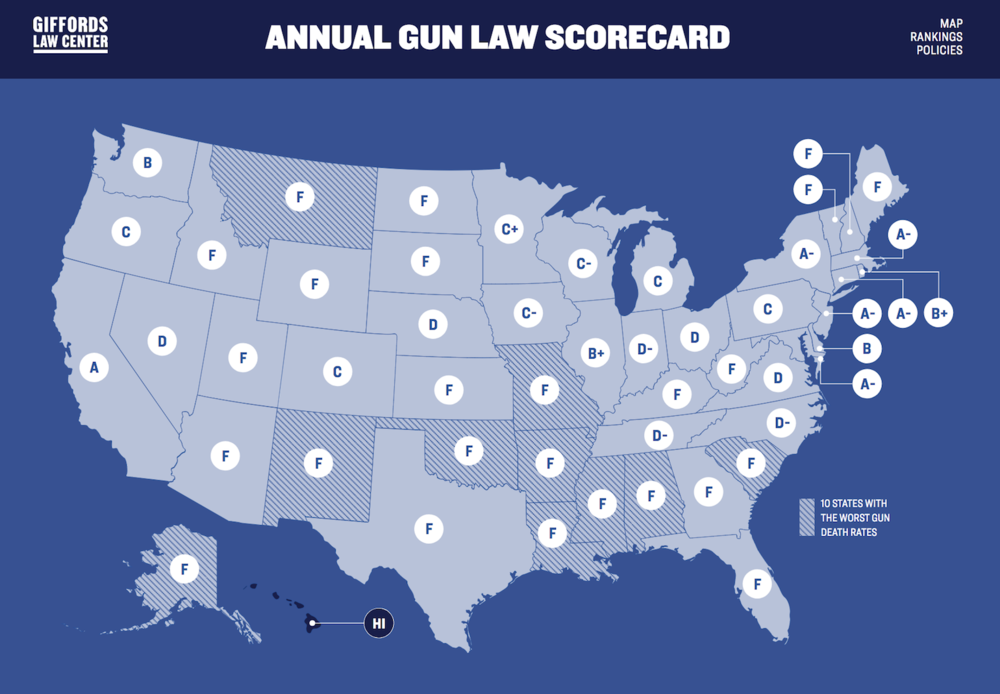

Check out how your state rates on gun control with this Scorecard provided by the Giffords Law Center

Check out how your state rates on gun control with this Scorecard provided by the Giffords Law Center

For gun control groups aiming to thwart the NRA and tighten controls, advertising dollars alone have not been enough.

“White House efforts to strengthen gun-control laws went nowhere,” stated Kantar Media in an article by AdAge. Watered-down legislation to broaden FBI background checks of gun buyers failed in the Senate, AdAge reported, and the GOP-controlled House did not even consider addressing gun-control legislation. The investment return on advertising has been very weak for gun control groups, Elizabeth Wilner of Kantar Media told AdAge in 2013. “When you are doing advocacy advertising you are looking for Congress to pass something.”

Some speculate that Bloomberg’s advertising may have backfired. Targeted politicians wore his condemnation as “a badge of honor,” Jeb Golinkin wrote in the US edition of The Week, a British news magazine that same year. One Democratic politician, former Arkansas Sen. Mark Pryor, even ran an ad bragging about it.

creating the debate

Another area of concern lies with creative agencies themselves.

In 2015, for instance, New York-based Grey Global Group produced an award-winning campaign titled The Gun Shop: A pop-up gun store where customers were shown the history behind each gun — such as suicides, homicides, unintentional and mass shootings — and their stunned reactions were captured via hidden cameras. The ad had 13 millions views, and Grey says it resulted in a 3000% increase in donations and a 1250% increase in signed petitions. It “wowed the media & changed minds,” the firm’s Web site shows, with 80% of the shoppers deciding against owning a firearm.

Here’s the catch: Grey is owned by holding company WPP. A report last year by The Guardian showed PR firms owned by WPP lobbied the US government for years on behalf of the National Rifle Association while its agencies simultaneously made and promoted ads advocating for stricter gun control laws. Adweek reported the holding company did not directly confirm its relationships with the NRA, but said it represents clients on both sides of political issues. A Grey spokesperson declined comment, Adweek said.

Some observers suggest that gun control ads tend to focus on guns instead of the consequences of gun violence. Ads such as the spot Who’s There?, produced for Australian workplace safety organization Worksafe Victoria, are more impactful because they are more emotional, Jeremy Porter, a New York-based freelance communications strategist, wrote in a 2013 blog. The ad shows police arriving at the home of a child whose father is not coming home — and even though we don’t know why, the scene between the child and one of the police officers is gripping.

“Guns hurt. They hurt the people they are aimed at, they hurt their family and friends who learn to live without them, they hurt complete strangers who see how avoidable this is. You don’t have to be shot to be affected by gun violence,” Porter wrote. “This is where I think gun control advocates could be doing better: appealing to people’s emotions, not rational thought.”

Even when that is achieved, and even when a majority of Americans are in favor of stronger gun control measures, it’s still difficult to shift long-held public opinions. In 2015, for instance, Annenberg School of Communication Professor Diana Mutz ran a project in her Media and Politics class involving gun control. It required her students to craft 30-second video ads that were then professionally tested on a national sample of respondents online. Despite some innovative ideas, only three of the eight videos produced a statistically significant response — and even those created very small effects (less than half a point on a five point scale).

The failure of gun control advertising to affect significant change is not for lack of trying. From serious to satirical, advertising agencies and nonprofit gun control groups have experimented in recent years with just about every genre to turn the tide of public opinion and impact legislation.

States United to Prevent Gun Violence tricked action movie fans into a screening of Gun Crazy, which was billed as a blockbuster but turned out to be real footage of gun violence. A PSA called “Playthings”, produced for the gun safety group Evolve Together, showed two boys fighting in the front yard with vibrators instead of guns. A PSA titled “Keep America Safe” for the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence suggested (satirically) that we jail toddlers with access to guns in homes so they stop shooting parents.

In December 2016, a notably subtle ad sponsored by Sandy Hook Promise showed a bored high school student named Evan etching words into a library table. Someone writes back, and we assume it is a brewing romance. We aren’t thinking about the student behind Evan who is reading a gun magazine in one scene, then watching a sniper video in another, and finally turning up inside the school with an assault weapon. “While you were watching Evan, another student showed signs of planning a school shooting,” the ad reads. “But no one noticed.”

moving the needle

In the aftermath of the Parkland school shooting, major companies began severing ties with the NRA – from First National Bank of Omaha, the nation’s largest privately held bank, to car rental companies and global airlines. On February 28, Dick’s Sporting Goods announced it would no longer sell high-capacity magazines and would not sell guns to anyone under 21 years of age, regardless of local laws. Walmart followed suit, ending the sale of guns and ammunition to anyone under 21. The outdoor retailer REI also suspended its relationship with a company that supplies some of its most popular brands, including CamelBak and Giro, because the conglomerate also manufactures guns and ammunition.

A new generation – led by Parkland survivors – also are calling for sweeping legislative changes (#neveragain). Still, high school students alone are unlikely to bust apart the NRA narrative, wrote Bill Scher in Politico last month. In fact, it wasn’t until this week that Oregon enacted America’s first new gun control law since the Parkland massacre, a bill prohibiting domestic abusers and individuals under restraining orders from owning firearms.

So, what’s the solution?

Scher suggested taking a page from the anti-tobacco movement’s successful Truth Initiative campaign that turned the image of smoking from cool rebellion to corporate dishonesty. It is widely credited for helping drive smoking levels among teens down from from 23 percent to 6 percent, even in Hollywood, which was pressured to stop making cigarettes look cool, Scher noted.

“Such a campaign would have two main objectives: In the short run, keep the gun control majority engaged on a daily basis, and in the long run, reduce the demand for guns in areas where the NRA exerts political influence,” Scher wrote. “Until there is a gun-free culture that can rival what the NRA has cultivated over decades, no national trauma, no matter how searing, is going to move the political needle.”