The last time SAG-AFTRA and the WGA collectively went on strike was in 1960, and…

Times Of Transformation: Art Imitates Life As Gender Is Redefined

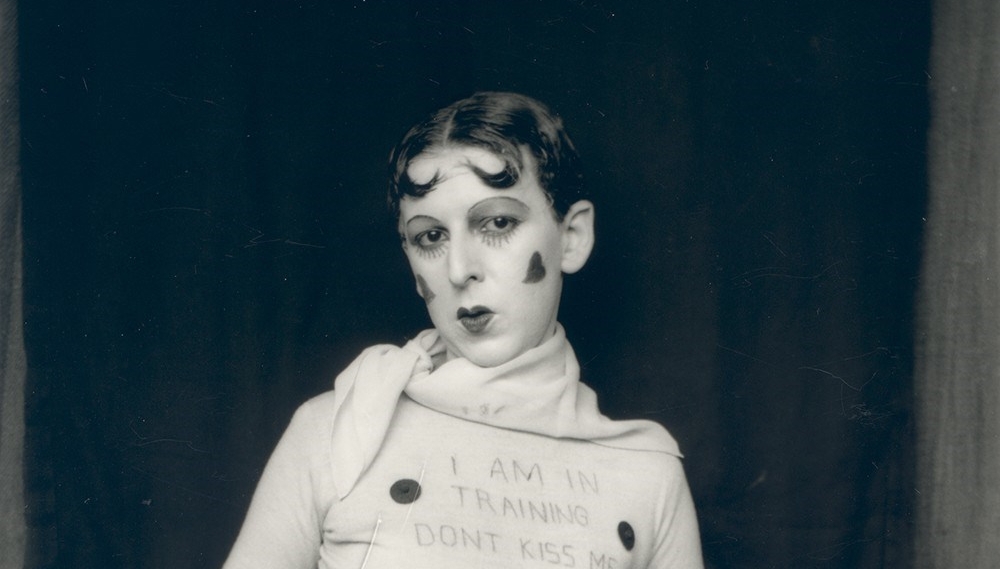

Shuffle the cards. Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neutral is the only gender that always suits me. – Claude Cahun (1854 – 1954)

Just over a century ago in 1911, two photographers began experimenting with self-portraiture and the taboo subject of gender identity and authenticity in Europe between the First and Second World Wars. Adopting male pseudonyms, Claude Cahun (born Lucy Schwob) and Marcel Moore (born Suzanne Malherbe), the two artists – also lovers, step-sisters and members of the French Resistance – showed how a single human body is able to obscure gender, with Cahun posing in everything from hyper-feminine, theatrical makeup and swooping kiss curls to hyper-masculine three-piece suits.

Despite the iconic, gender-bending performances of Marlene Dietrich, well-known at the time, Cahun and Moore failed to identify as mainstream. Their work was never exhibited during their lifetimes, coming to light decades later in the 1980’s.

In what might be the most significant attempt by a major museum to tackle the subject of gender fluidity in contemporary art, Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon opened last month on September 27th at the New Museum. The exhibition gives voice to over 40 intergenerational and multi-disciplinary artists investigating “gender’s place in contemporary art and culture at a moment of political upheaval and renewed culture wars.” The collective work explores “gender beyond the binary to usher in more fluid and inclusive expressions of identity.”

If Trigger brings to mind the politically-fraught, AIDS-inspired performance art of the 80’s, think again. These artists – many of whom are commissioned – are working off a new platform of resistance, what curator Johanna Burton describes as “beauty and pleasure” over the stock political agenda.

Back in Manhattan, performance artist Justin Vivian Bond strikes a pose in the window of the New Museum, donning a glittering pink cocktail dress and heels in My Model | My Self: I’ll Stand By You. Behind him hangs hand-drawn wallpaper, setting the face of his idol, the model Karen Graham, against his own. His intent, as explained by Bond in a recent New York Times article, is to put a “’queer face’ on the glamour created by gay people that has long been appropriated by mainstream culture.”

Just a short walk away, artists Candice Lin and Patrick Staff pump testosterone-reducing, plant-based tinctures into the lobby of the New Museum as part of their work, Hormonal Fog. Photographer Sadie Benning both literally and figuratively blurs gender identity in her portrait series Rainy Day/Gender, photographing subjects through droplets of rain on a windshield. And sculptor Ektor Garcia draws on fetishism and Mexican housewares to encourage movement away from conventional definitions of gender and sexual roles.

“Your terms, what you’re trying to do, does not reflect my reality”

As notable as Trigger is for curators, artists, and contemporary audiences alike, make no mistake that gender fluidity has long-contributed to the human experience, although a particularly tough pill to swallow in western cultures. From the Köçek dancers of the Ottoman Empire, who were considered a third gender, to the inhabitants of Sulawesi, Indonesia, who themselves recognize five genders, there’s no shortage of historical, cultural and anthropological references. Even so, an approach to gender fluidity that encourages awareness, acceptance, and understanding is conspicuously absent from the American cultural mainstream.

which begs the question, why now?

Not surprisingly, the answer lies in both the current political climate and the values of rising generations. Debates around transgender public bathrooms, Caitlyn Jenner’s gender confirmation surgery, and the rights of transgender personnel to serve in the military bring a “new level of visibility to gender-fluid artists who have only been acknowledged before in a trickle of mainstream shows,” explains Hilarie M. Sheets. Gender fluidity “has become native to young people who are used to constructing their own identities on social media and declaring their preferred personal pronouns on college campuses and at workplaces,” she says.

“There have been generations that have lived by the rules and those generations that break the rules,” adds GLAAD President and CEO Sarah Kate Ellis. Young people today are “redefining everything.” A recent GLAAD survey reinforces Ellis’ point. Twenty percent of millennials believe they are “something other than strictly straight and cisgender, compared to seven percent of boomers,” TIME reports. “They believe that both sexuality and gender are less like a toggle between this-or-that and more like a spectrum that allows for many – even endless – permutations of identity.”

Younger generations are “not just saying ‘screw you,” quotes Ritch Savin-Williams, Professor Emeritus of Psychology at Cornell University. “Their embrace of a vast array of identities says, ‘Your terms, what you’re trying to do, does not reflect my reality or the reality of my friends.’”

And yet, the increasing focus on gender authenticity in contemporary arts culture does just that. The result is a beautiful thing.