The gig economy is alive and well. In fact, this modern online phenomenon has only…

The Art of Stealing: Flattery or Fraud?

“Good artists copy, great artists steal,” Pablo Picasso famously stated. A great quote, but when it comes to great art, where does the line fall between copying, reimagining, and stealing? Basically the same thing, right?

Whether a subtle nod to an artists’ muse or the more outspoken and obvious repurposing of creative content, the undertone of flattery is inherent. While “copying” may force artists, audiences and historians to question the validity or originality of a piece of work, it is an equal display of admiration and respect.

A given artist is likely not the first to dabble in a particular style, method, or subject matter. But it is their specific voice, their ability to draw on their surroundings and to reflect on an original concept or the work of their peers, that allows that method, subject matter or style to become theirs alone.

Some of the most well-known names in art history, from Lichtenstein to Picasso, have been accused of stealing their creative spark from peers. Does this invalidate their work? Or did they instead adopt new filters and hone their artistic processes, improving on the styles of others and inspiring future generations?

“[T]here are still people who believe that Lichtenstein – the so-called architect of pop-art celebrated for his distinctive cartoon style – was a copycat, not an artist,” explains Alastair Sooke in his article for the BBC. Sooke does not agree.

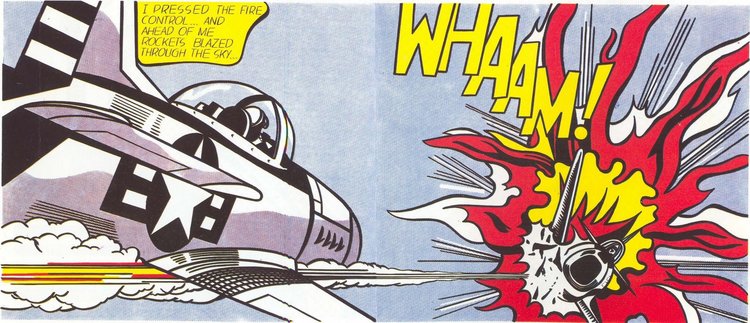

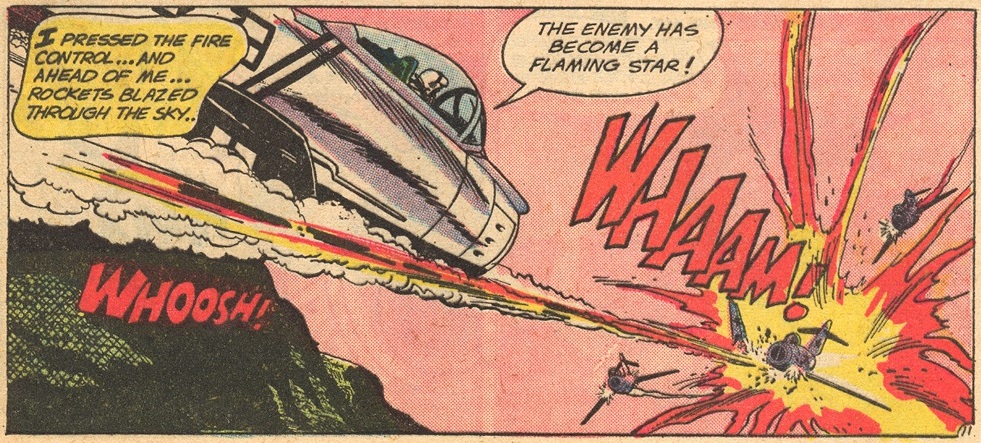

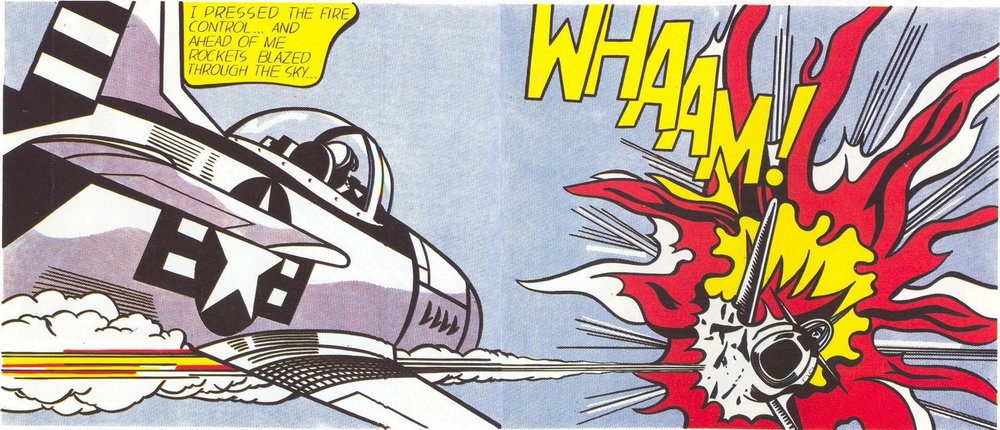

Whaam!, originally illustrated by comic-book artist Irv Novick, is a perfect example of where one artist infuses their style and voice on another artist’s’ work, blurring the lines between originality and copycat. Lichtenstein’s reimagining of Whaam! In 1963 secured him as a solid figure within the annals of pop-art history. “Lichtenstein transformed Novick’s artwork in a number of subtle but crucial ways […] while Novick’s explosion is a measly, scratchy little thing slipping out of a frame, Lichtenstein’s self-possessed fireball unfurls like a blooming flower. Lichtenstein changed the colour of the letters spelling out ‘Whaam!’ from red to yellow, so that yellow would become another means of yoking everything together […] then, of course, there is the question of scale. Lichtenstein took something tiny and ephemeral – a throwaway comic-strip panel that most people would overlook – and blew it up so that it was a substantial oil (and acrylic) painting […] here, he was saying, was a contemporary equivalent of a grand ‘history painting.’”

There we have it in a nutshell: work that is repurposed, improved, copied, borrowed, reimagined, stolen. Subsequently, Whaam! No longer belongs to Novick in the hearts and minds of pop-art connoisseurs; it is instead definitively Lichtenstein’s creation.

Much like the work of Andy Warhol, Lichtenstein’s body of work is easy to source. But Pablo Picasso?

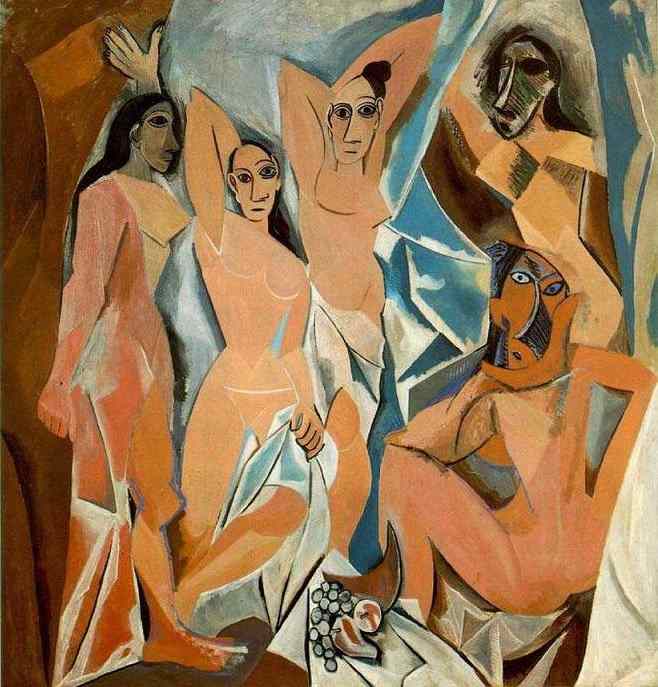

In the early 1900s, traditional African sculpture became a potent influence among European artists and a highly pivotal tool in the evolution of modern art. Pablo Picasso, along with his peer Henri Matisse, “blended the highly stylized treatment of the human figure in African sculptures with painting styles derived from the post-impressionist works of Edouard Manet, Paul Cezanne and Paul Gauguin,” explains PabloPicasso.org. “The resulting pictorial flatness, vivid color palette, and fragmented Cubist shapes helped to define early modernism.”

Not everyone is quite so generous in describing Picasso’s penchant for stealing. In 2006, the Telegraph reported that “the first significant exhibition of Pablo Picasso’s work in South Africa has provoked a furious row after a senior government official accused him of stealing the work of African artists to boost his ‘flagging talent.’”

Apparently, you can’t please all people all the time. For Picasso, pleasing the vast majority of them may just be good enough.

Where and how great artists choose to draw inspiration is just one ingredient in their ultimate success. Where and when the lines blur between stealing, copying, and infusing a past work with one’s own stylistic overtones is a question we have yet to answer.