The gig economy is alive and well. In fact, this modern online phenomenon has only…

Branding Disabilities: Going Mainstream

One look at graphic designer Alexis Meinhold’s Pinterest board, and you get the idea: A 30-something Manhattanite with idiopathic neuropathy who wants J. Crew to sell walking canes. Concrete subway steps painted with the image of Mt. Everest asking for help to build more handicap facilities.

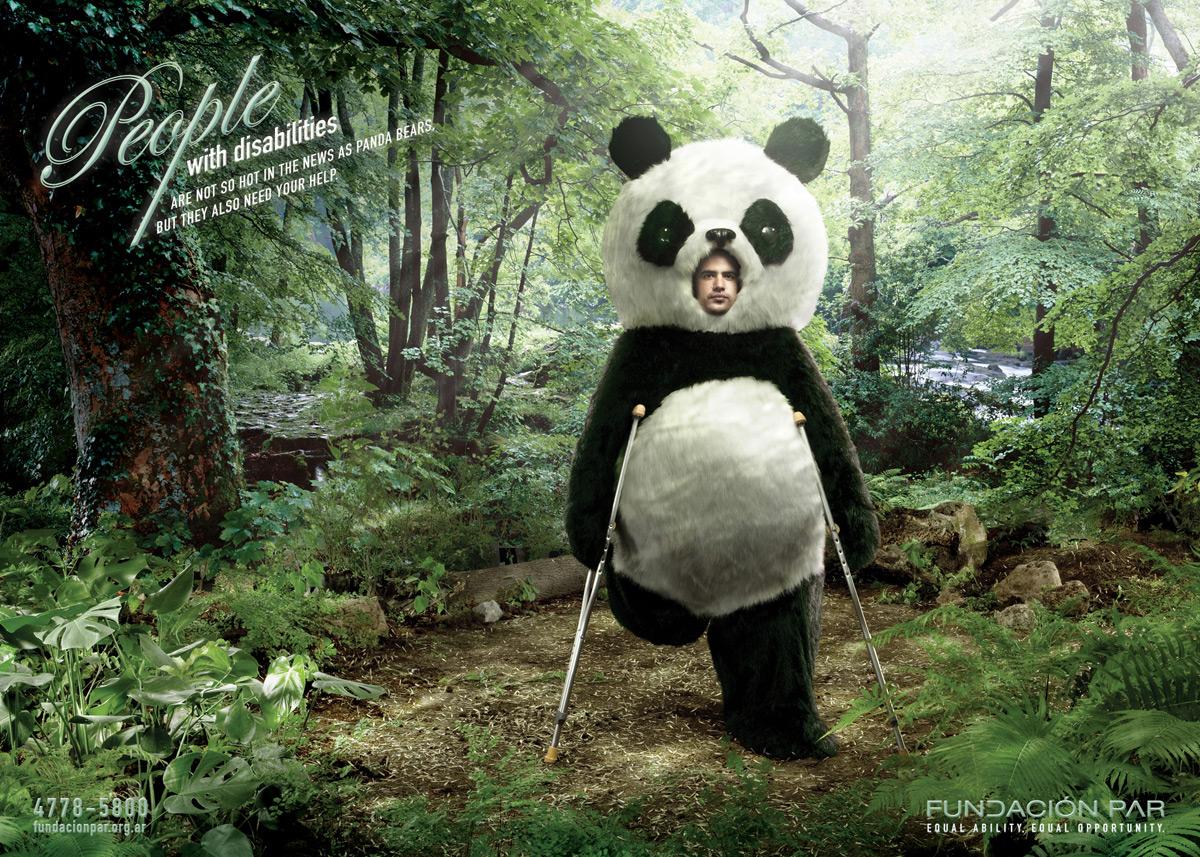

Two girls, one with Down Syndrome, all smiles as they sit on a bench together wearing Livie & Luca summer sandals. A one-legged man in a panda suit walking with a pair of crutches through a forest.

“People with disabilities deserve concern and coverage equivalent to those given to endangered species,” the ad reads.

Disability, like multiculturalism, is finally making inroads in the advertising world as more and more national brands recognize the power (and compassion) of inclusiveness and its money-making potential. One in 5 people in the US have a disability, according to the 2010 census, while slightly more than one-quarter of today’s 20-year-olds will become disabled before they retire.

a profitable pivot

The discretionary spending power of disabled individuals is an estimated $220 billion—more than the African‐American, Latino, and LGBTQ markets combined. The disability market also offers double the fabled spending power of teens and more than 17 times that of tweens (8‐ to 12‐year‐olds), two of the most attractive demographic groups for marketers.

In a 2016 survey of households with people who have disabilities, Nielsen reported that while they skew lower income, they actually make more shopping trips and spend more per trip on average than other households. They also have greater brand loyalty because they are less likely to use coupons or buy products at a discount, the survey showed.

There were early signs of that potential when, in 1998, Mattel sold out of its Share-a-Smile Becky (Barbie’s companion in a wheelchair) in mere weeks. More recently, when Mars grew its Maltesers brand by 8% after launching three UK ads focused around disability during the 2016 Paralympics Games, the company said it was its single most successful campaign in at least a decade.

A key to that success is treating individuals with disabilities as part of the mainstream consumer market and not a small subgroup. Another part is recognizing that most consumers know and care about someone who is disabled, whether that’s a family member, friend, caregiver, or colleague.

Fisher-Price, for instance, began using child models with Down syndrome in 2015 due to the increasing diversity of its global customer base.

“The consumer mind-set has really changed,” Teresa Gonzalez Ruiz, Vice President for the company’s brand marketing, told The New York Times. “Millennials are so in tune with causes. The biggest shift I’ve seen as a marketer is that in the past three to five years of talking to moms, they care about the product but they also really want to know where the company stands.”

steps forward

Disability advertising has struggled for many reasons, including perceived public discomfort or companies fearing they would stigmatize their product or do it wrong (and some have). Clearly, disability’s absence from major advertising also has to do society’s fixed ideas about what constitutes an “acceptable” or ideal appearance.

Added to that, the Americans with Disabilities Act, while creating inroads for accessibility, led to lawsuits that generated marketers’ fears about liability. But as those waned, an increasing number of brands have stepped up to make disability an integral part of their product messaging and to reflect the lifestyles of disabled people in their national campaigns.

For instance, after a serious misstep, Lego introduced a Fun in the Park character who uses a wheelchair. Across the ocean, McDonald’s Sweden used jumbled letters on ads and menus to simulate dyslexia and raise awareness about the disability.

To name a few others:

- Tommy Hilfiger’s accessible clothing line “Adaptive” is marketed for its easy-to-dress magnetic snaps and pant leg openings for those using crutches or wearing prosthetics.

- Microsoft’s Xbox Adaptive Controller is billed as a device to meet the needs of gamers with limited mobility.

- Grace Beauty is lauded for its mascara brushes with improved grips for “all kinds of users.”

making it work

For disability branding to be effective, and not backfire (like Nike’s 2000 Air Dri-Goat running shoe ad), it needs to be backed not only by a genuine understanding of disabilities but also a robust diversity and inclusion strategy.

After the success of Mars’ Maltesers campaign, account director Philippa Field told AdAge that it “felt like a really interesting way to subvert some of the usual representations of disability in advertising, using the power of humor to break down taboos and prejudices.”

“The main challenge was learning enough about people living with disability to make the executions feel authentic and relatable,” she said.

Consumers, especially members of the disability community, recognize when companies value hiring and promoting people with disabilities and go out of their way to support local disability programs.

In other steps, a group of ad industry leaders joined forces two years ago to launch a US branch of Creative Spirit, an Australian nonprofit dedicated to matching people with disabilities with careers at creative companies. The group is seeking to create 130,000 fair wage jobs for those with intellectual and developmental disabilities by 2020.

“We all need to take responsibility and do our part,” Laurel Rossi, the US group’s founding executive director and mother of a daughter with Williams Syndrome, told AdAge.

Another group, Changing the Face of Beauty, has more than 100 companies committed to using models with disabilities in their advertisements.

“We focus on what a smart business decision it is to include people with disabilities in advertisements,” founder Katie Driscoll of Chicago told The New York Times. “You are essentially leaving a lot of money on the table, otherwise.”