The last time SAG-AFTRA and the WGA collectively went on strike was in 1960, and…

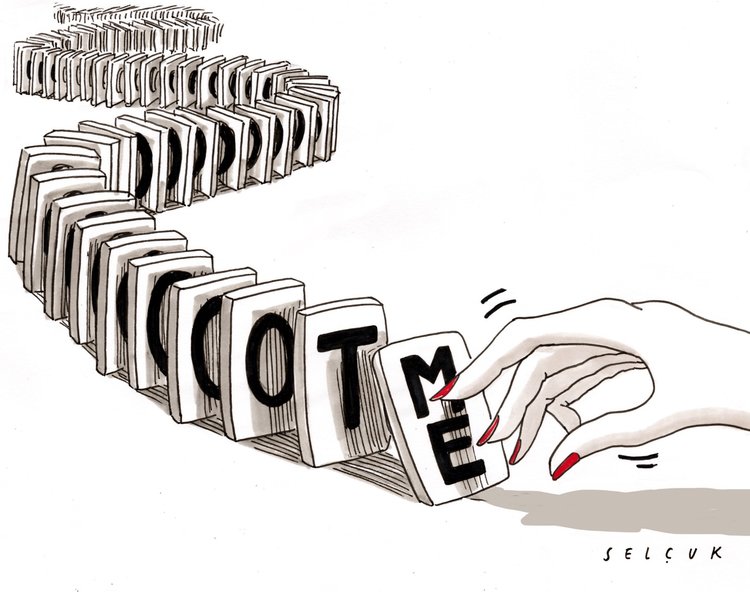

The Economic Costs of #MeToo: Quantifying a Movement

Les Moonves, the longtime CBS chairman and CEO, is out as the latest #MeToo casualty in the wake of sexual assault and abuse allegations detailed by The New Yorker’s Ronan Farrow. Harvey Weinstein, Matt Lauer, Charlie Rose, Roger Ailes, Bill O’Reilly, Louis C.K., and Kevin Spacey – also gone, but not forgotten.

As the list continues to grow, so does the outrage and price of keeping a sexual abuser on the payroll. Just consider the astoundingly low opening receipts of Spacey’s latest film release, Billionaire Boys Club: $126.00. Not $126 million, or thousand, but just 126 dollars. Less than the cost of a new pair of designer jeans.

If you wondered how much Spacey (who denies the allegations) would suffer, you can now do the math — from the dismissal of his titular character Frank Underwood on House of Cards to Ridley Scott’s $10 million dollar decision to replace Spacey with Christopher Plummer amid boycott calls against the 2017 film All the Money in the World.

“When you’re in film, it’s a lot of money to lose if it’s not working,” Scott told The Guardian. “Business is always highly linked with the creative process.”

Consider these examples:

-

Netflix reportedly lost $39 million for cutting ties with Spacey.

-

Twenty-First Century Fox disclosed in May 2017 that in the nine months leading up to March 31, it had incurred $45 million in costs tied to litigation related to harassment allegations. (Advertisers from BMW to GlaxoSmithKline, meanwhile, fled Bill O’Reilly’s show amid sexual misconduct allegations against the former Fox News host.)

-

The Weinstein Company was forced to sell its North American distribution rights to “Paddington 2” to avoid bankruptcy.

-

Hours after Kate Upton via Twitter accused Guess co-founder Paul Marciano of using his power to “sexually and emotionally harass women,” the company’s shares dropped almost 18%. The upshot? Guess lost more than $250 million in market value in one day.

-

That’s chump change to Wynn Resorts, which lost $3.5 billion in value after sexual harassment allegations surfaced about casino mogul Steve Wynn.

More than 200 celebrities, politicians, CEOs and others have been publicly accused of sexual misconduct under the #MeToo banner since April 2017. But what about other below-the-radar cases in a country where an estimated one in three people – 31% – experience sexual harassment on the job?

Harassment takes a physical and psychological toll on victims akin to being exposed to excessive health hazards or suffering a serious injury or illness. What we don’t know are the total economic costs to individuals and companies in the U.S. due to sexual misconduct in the workplace – from lost pay and legal fees to decreased productivity, job turnover, and reputational harm.

The costs of decency are trivial; the rewards to shareholders are large.

A group of Democratic senators led by Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.), asked the Department of Labor earlier this year to collect data on the prevalence and cost of sexual harassment in the workplace. The department refused, saying that “collecting this information would be complex and costly.”

But as author and cultural theorist Lynn Stuart Parramore points out, new information associated with #MeToo provides a “golden opportunity” to unearth exactly that type of important data. Chances are that understanding the economic consequences of sexual harassment in the workplace would cause it to be taken more seriously before and after it occurs.

Costs are likely to increase as the #MeToo movement continues to grow and laws governing non-disclosure agreements and statutes of limitations change to ease restrictions on reporting abuse.

We may not know the exact figures, but it’s reasonable to assume they‘re high. In a 2016 report, The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission said it had recovered more than $164 million for workers alleging some type of harassment the previous year, though it acknowledged complaints were likely significantly underreported. Years earlier, a 1994 US Merit Systems Protection Board study estimated that sexual harassment cost the federal government about $325 million — the equivalent of $556 million today — over a two-year time period. These amounts also fail to take into account all the private settlements granted in secret.

Since the onset of #MeToo, there’s been a 2% increase in women asking for a raise or promotion, according to a June survey by Challenger, Gray & Christmas of 150 HR executives worldwide. Women clearly bear the brunt of sexual misconduct at work, often finding their careers derailed and reporting increased financial distress.

Up to 85% of women reported being sexually harassed at work, according to the 2016 EEOC report. According to research from sociologists Heather McLaughlin, Christopher Uggen, and Amy Blackstone, women who experience harassment are 6.5 times more likely to leave their jobs than those who do not.

The department refused, saying that “collecting this information would be complex and costly.”

“Workplace harassment first and foremost comes at a steep cost to those who suffer it, as they experience mental, physical, and economic harm,” the EEOC report stated. “Beyond that, workplace harassment affects all workers, and its true cost includes decreased productivity, increased turnover, and reputational harm.”

These broader costs take various forms. Companies are purchasing “employment practices liability insurance” to cover costs associated with employment lawsuits, according to David Yamada, Professor of Law and the Director of the New Workplace Institute at Suffolk University. For a media company with 20,000 employees, a pre-#MeToo deductible fell around $2.5 million. Now that number has doubled to $5 million, liability expert Tom Hams told Forbes.

According to Risk Management Prof. Michael McCloskey at Temple University, many insurers took an even harder stance in the wake of the Weinstein scandal, rejecting requests from studio production companies for updated employment practices liability insurance policies. Some insurers are choosing to provide training materials, demanding (and checking) that companies institute anti-harassment policies and procedures – a costly budget add-on.

Women who experience harassment are 6.5 times more likely to leave their jobs than those who do not.

Other costs due to sexual misconduct are less tangible, less quantifiable, but carry just as much – if not more – weight on society. The outflow of potential talent, ideas and investments, which either find new places to thrive or go missing altogether.

“Even if one leaves aside all moral arguments — which one should not — failing to deal with harassment is usually bad for business,” the Economist wrote. “Firms that tolerate it will lose female talent to rivals that do not, and the market will punish them. The costs of decency are trivial; the rewards to shareholders are large.”

“As people drop out, opt out, and tune out of their chosen fields, it affects the whole economy,” writes Nilofer Merchant in the Harvard Business Review.

“It’s the missing female Harvey Weinstein who never got a chance to shape the full range of stories of our society. It’s the female Charlie Rose who never got a chance to earn the power and influence associated with that role,” Merchant wrote. “And moving away from the hypothetical, it’s the Susan Fowlers and Ellen Paos who didn’t get to build the companies or make the investments that offered the new solutions that society most desperately needs.”